Would Europe want to suppress weapons ?

samedi 25 mai 2019, par ,

This article is a work in progress. I am offering it up for comments/suggestions. It will be presented on June 15th, 2019 during the annual congress of the FESAC for additional amendments before it is sent out to all E.U. stakeholders.

We just voted to send almost sixty deputies to the E.U. Parliament. And we are disappointed by the general lack of interest from candidates. Only one candidate responded to the questionnaire we sent to him, and in a way that gratifies amateurs. But what about others ?

We are profoundly worried. The E.U.’s stand against firearms is so extreme that it appears intent on doing away with this basic freedom entirely.

One of our colleagues recently heard a scary piece of intel in a hallowed hall of the E.U. : for the next amendment of the law, the commission plans on transitioning to two categories. We know what this points to : prohibition or subject to licensing. And then there’s the Czech Republic’s appeal against the Commission’s Anti-Weapon Directive filed with the European Court of Justice.

And then there’s the Czech Republic’s appeal against the Commission’s Anti-Weapon Directive filed with the European Court of Justice.

The General Counsel of the ECJ has stated that possessing firearms in the E.U. is not a fundamental right [1]

Obviously, we do not agree with him. In a liberal and democratic system like the E.U.’s, « freedoms are the principle, and restriction by police the exception » [2]

The balance between safety and freedoms is the dilemma of all governments everywhere. Order must prevail for freedoms to be regulated, this goes without saying. If freedoms were absolute, anarchy would take over, and a society governed by fear and chaos is necessarily deprived of freedoms. However, if freedoms are totally muzzled because of safety, then they become non-existent, and a state without freedoms becomes a totalitarian state.

The balance between safety and freedoms is the dilemma of all governments everywhere. Order must prevail for freedoms to be regulated, this goes without saying. If freedoms were absolute, anarchy would take over, and a society governed by fear and chaos is necessarily deprived of freedoms. However, if freedoms are totally muzzled because of safety, then they become non-existent, and a state without freedoms becomes a totalitarian state.

It is therefore crucial to find the right balance between these two concepts, insofar as restriction by law enforcement must always guarantee the freedoms that it restricts. While this would appear to pose a big paradox, it is now clear that freedoms and safety are not supposed to oppose, but regulate, each other. In this sense, it is up to the state to ensure the safeguarding of an order that’s respectful of the rights and freedoms for everyone. Nevertheless, since police action is the exception to the principle of freedom, it must be limited and proportionate. Indeed, this rule remains the foundation of a democratic society and of a peoples who aren’t suffering under the oppression of the state. [3]

And with good reason since, according to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, « man is born free and everywhere he is in chains » [4]. So, to him, « to find a kind of association which defends and protects from the whole common power the person and the property of each of partner, and by way of which each, uniting with all, obeys nevertheless only to himself and remains as free as before. This is the fundamental problem which the Social Contract provides the solution to » [5]. Thus, clearly, in the Social Contract, everyone renounces his natural freedom to gain a civil liberty ! The Social Contract proposed by Rousseau establishes that everyone give up his private rights (or that of the strongest) in order to obtain rights equality as provided by a society that guarantees its full realization. More precisely, the legitimacy of the social contract is therefore based on the fact that man does not literally alienate his natural right, but understands that the social pact is, on the contrary, the condition of the actual existence of his natural rights.

And thus, honest citizens who legally bear firearms must be able to freely dispose of their property and have access to it at their leisure, in accordance with the E.U. laws that are supposed to protect them from arbitrariness and guarantee their basic rights.

To this end, we have prepared a proposal for an amendment to the bill and we will be asking all E.U. actors to apply pressure on their representatives to enact it or have it submitted for review. If our voices are united, loud and clear and come from all over Europe, then we’ll be able to have a chance to influence the debate. This already worked out, partly, as pertains to the latest amendment to the bill.

This is the initial phase of our effort, things may be modified down the road. Let’s wait for the final conclusions of the next FESAC congress before getting involved.

Proposal in favor of the 91/477/CEE Directive related to the enforcement of firearms purchased and owned by citizens legally holding firearms.

Proposal in favor of the 91/477/CEE Directive related to the enforcement of firearms purchased and owned by citizens legally holding firearms.

During the informal meeting of the E.U. Council of February 12th, 2015 following the terrorist attacks that took place in France, government heads asked all competent authorities to reaffirm their cooperation in the fight against the illegal firearms trade, in particular by quickly reviewing all applicable laws and triggering once again the debate on matters of security with developing countries, especially those located in the Middle East, North Africa and the Baltic States regions.

Following the meeting of the « Justice and Domestic Affairs » committee of March 12th and 13th 2015, ministers invited the commission to submit new methodologies for combating illegal arms trafficking and intensifying, in conjunction with Interpol, operational cooperation and the exchanging of intelligence.

Following this, the Commission took the decision to reassess firearm laws, emphasizing the challenges posed by the illegal arms trade and recommending that urgent measures be taken to prevent firearms that had been deactivated from being reactivated again and used by criminals.

The commission then passed Executive Order 2015/2403 (December 15th, 2015), which establishes common policy concerning guidelines and techniques for deactivation, with a view to ensure that deactivated firearms are rendered irreversibly inoperable. The Commission then submitted to Committee a project that became the (UE) 2017/853 Directive of Parliament and on May 17th, 2017 the Committee amended the 91/477/CEE directive of the Counsel as relating to the enforcement of firearms holding and purchasing.

These amendments, however, drafted in a hurry in the wake of catastrophic terrorist attacks, are detrimental to the rights and freedoms of honest citizens of the E.U. who legally own firearms for recreational, or for self-defense purposes when law enforcement isn’t immediately available and their lives are being threatened.

As it were, in principle, the E.U. promotes and reinforces the protection of rights and freedoms of European citizens, particularly, as is expressed in the E.U.Charter of Fundamental Rights. In this regard, Article 6 of the Treaty of the European Union states,

- « 1. The Union acknowledges the rights, the freedoms, and the principles as stated in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of December 7th, 2000, as it was established on December 12th, 2007 in Strasbourg, that which has the same legal value of the treaties (...)

- 2. The Union adheres to the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights And Fundamental Freedoms (...)

- 3. Fundamental rights, as guaranteed by the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights And Fundamental Freedoms and as they result from constitutional traditions that are common to member-states, are a part of the legal framework of the Union as guiding principles. »

Moreover, in its preamble the E.U.’s Convention for the Protection of Human Rights And Fundamental Freedoms states, « The Union contributes to the preserving and the developing of these common values in respect to the diversity of cultures and the traditions of peoples of Europe, » and, « this present charter reaffirms, in the respect of competencies and tasks of the European Union, as well as of the principle of subsidiarity, rights which are the result, specifically, of constitutional traditions and international obligations shared by member-states, of the European Union Treaty and of regional treaties, of the European Convention on Safekeeping of Human Rights and Fundamental freedoms, of the Social charter as was adopted by the union and by the European Counsel, as well as by the jurisprudence of the Court of Justice of the European regions and the European Court Human Rights court. »

Except that Articles 24 and 27 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 7 of the International Pact related to economic and social rights, as well as articles from the constitutions of a great number of E.U. member states, mention this right to leisure for citizens :

- Paragraph 11 of the Preamble of the 27th October 1946 constitution, itself which refers back to the Preamble of France’s constitution of 4th August 1958 ;

- Article 59 of Portugal’s 2nd April 1976 Constitution

- Article 23 of Belgium’s Constitution of 17th February 1994

- Article 22 of the Netherlands’ Constitution of 17 February 1983 ;

- Article 69 of the Constitution of the Republic of Croatia of 22 December 1990 ;

- Articles 23 and 54 of the Constitution of the Republic of Bulgaria of 13 July 1991 ;

- Article 73 of the Republic of Poland of 2 April 1997... But hunting, different types of sports shooting, or, collecting, are the types of recreational activities that legal citizens of the E.U., who are legal holders of firearms, should be able to partake in freely without obviously disproportionate amendments getting in the way of this.

By the same token, Article 17 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 1 of the additional protocol to the European Convention of the Safeguarding of Human Rights, Article 17 of the E.U.’s Fundamental Rights charter, as well as the articles of the Constitution of numerous member-states, mention the respect of the right to property arms for citizens :

- Articles 2 and 17 of the Human and Citizen Rights Declaration of the 26th of August 1789, to which the Preamble of the French Constitution of the 4th of August 1958 refers,

- Article 14th of the fundamental law of the Federal Republic of Germany of 23rd of May 1949

- Article 33 of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Spain of 27th of December 1978

- Article 62 of the Portuguese Republic of 2nd of April 1976

- Article 42 of the Republic of Italy of 22nd of December 1947

- Articles 16 and 17 of the Belgian Constitution of 17th of February 1994

- Article 14 of the Constitution of the Netherlands of 17th February 1983 ;

- Article 16 of the Constitution of Luxembourg of 17th October 1868 ;

- Article 15 of the Finnish Constitution of 1st March 2000 ;

- Article 11 of the Charter of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms referred to in the Constitution of the Czech Republic of 16th December 1992 ;

- Article 33 of the Constitution of the Slovenian Republic of 23rd December 1991 ;

- Article 48 of the Constitution of the Republic of Croatia of 22nd December 1990 ;

- Article 20 of the Constitution of the Slovak Republic of 3rd September 1992 ;

- Article 73 of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Denmark of 5th June 1953 ;

- Article 18 of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Sweden of 28th February 1974 ;

- Article 41 of the Constitution of the Republic of Romania of 8th December 1991 ;

- Article 17 of the Constitution of the Republic of Bulgaria of 13th July 1991 ;

- Article 64 of the Constitution of the Republic of Poland of 2nd April 1997

Moreover, honest citizens who own firearms for hunting, various forms of shooting sports or even collecting, should not see their right to property arms threatened, such as is the case today.

Finally, it should be noted that the Constitution of each state of the European Union mentions directly or indirectly the right to resist to oppression. Thus, eight countries of the European Union expressly and directly recognize the right of resistance to oppression, as is specified in :

- Article 2 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 26th August 1789 to which the preamble of the French Constitution of 4th August 1958 refers ;

- Article 4 of Title II of the Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany of 23rd May 1949 ;

- Article 21 of the Constitution of the Portuguese Republic of 2nd April 1976 ;

- Article 54 of the Constitution of the Republic of Estonia of 28th June 1992 ;

- Article 2-3 of the Constitution of the Republic of Hungary of 20th August 1949 revised ;

- Article 3 of the Constitution of the Republic of Lithuania of 25th October 1992 ;

- Article 32 of the Constitution of the Slovak Republic of 1st September 1992 ;

- Article 3 of the Constitution of the Czech Republic of 16th December 1992 and Article 23 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms of 16th December 1992 to which it refers.

Three countries (Ireland, Portugal and Slovenia) implicitly recognize in the preamble to

their Constitutions the right to resist. Other countries go even further, recognizing, not a

right, but a duty of resistance to oppression as stated :

- Article 11 of the Constitution of the Republic of Latvia of 10th December 1991 ;

- Articles 92 and 93 of the Constitution of the Republic of Poland of 22nd July 1952 ;

- Article 30 of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Spain of 27th December 1978 ;

- Article 6 of the Constitution of the Greek Republic of 9th June 1975.

Thus, the principle of resisting oppression (or self-defense), which includes the right to own a firearm as integral component to ensuring its effectiveness, constitutes « a constitutional tradition common to the Member States » and, as such, is a part of the « general principles of Community law, » the preamble to which is reflected in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the E.U. and Article 6 of the Treaty on European Union, signed in Maastricht on 7th February 1992, requiring compliance from one and all.

Especially since two countries of the European Union push the logic of the right to resist to its limit by expressly and directly acknowledging the right of every citizen to own a firearm, as specified here :

- Article I-7° of the British Bill of Rights of February 13th, 1689 ;

- Article 11 of the Constitution of the Republic of Latvia of 10th December 1991.

Estonia, for its part, expressly but indirectly acknowledges the right of every citizen to own a firearm in Article 48 of its Constitution by confining licensing authority to associations and businesses that own firearms or are military organizations only.

It should be noted, also, that freedom and security aren’t supposed to be opposites but rather, that they’re supposed to regulate each other. That said, police action being the exception to the rule of freedom must be limited and proportional. In fact, this rule remains the foundation of a democratic society and of a peoples that does not suffer oppression by the state.

It should be added that the aforementioned texts, where specifically concerns resisting oppression, acknowledge implicitly the right of every citizen to own a firearm when they talk about the right to undertake spontaneous actions, the obligation to act, to oppose and to forcefully push back any aggression when relying on law officers is impossible.

Moreover, one ought to be reminded that, in France, the right to bear arms constitutes a « natural right » of citizens in a democracy. In this sense, one should take note of the fact that there is an old law dating to July 19th 1792 of the fourth year of Freedom and a decree of July 17th, 1792 enacted by the National Assembly that was never repealed. However, this law and this decree specify that « in a free state, all the citizens must be provided with weapons of war, in order to push back, with as much ease as speed, the attacks of the internal and external enemies of their constitution ». In fact, the subject of firearms came up during the National Constituent Assembly of 1789. Indeed, at the meeting of July 28, 1789, Mr. Mounier, the member in charge of organizing the drafting of the Constitution, read Bill XVI as follows : « every man is allowed to repel force by force, unless it is used in virtue of the law. » This idea was later taken up in Article 11 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizens, which preceded the Constitution of 24 June 1793.

It should be added that the Constitution of June 24th, 1793 specified in Article 109 that « All the French are soldiers ; they are all trained in the use of arms, » it also added in Article 15 concerning the primary assemblies that « no one can attend armed. » It is clear, therefore, that, outside of assemblies, the carrying and possession of firearms was considered a natural right for all honest citizens. Similarly, the examination of the draft bill of rights that would become the Declaration of Human and Citizen Rights of August 26th, 1789 is quite enlightening, since Abbé Sieyes, then-Secretary of the National Assembly, specified in his Declaration of Rights bill that he presented on July 20th, 1789 that, « no citizen has more right than another to defend his life, his honor, his property. Thus, no public or private means of defense should be left to others exclusively. Thus, the bearing of arms, outside of military service and national exercises, belongs to everyone, or must be forbidden to all without exception » [6]

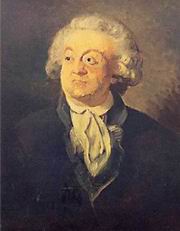

In addition, the Count of Mirabeau had proposed that a Bill X be passed as part of the draft by the « Committee of Five » that was responsible for the official drafting of the Declaration, as follows : « Every citizen has the right to to own firearms in his home, and to use them, either for the common defense or for his own defense, against any unlawful aggression which would endanger the life or liberty of one or more citizens » [7]. The members of the Committee even added that it was a « natural right » by stating that, « it is impossible to imagine an aristocracy more terrible than that which would establish itself within the State, and by way of which some citizens would be armed and other not ; that all the contrary reasonings are futile sophisms contradicted by facts, since no country is more at peace and offers a better police than those in which the nation is armed » [8]. According to the authors, « natural law is composed of a number of superior and intangible principles, which apply not only to the authorities of a particular State, but to the authorities of all States. Thus, the legislator, when making laws, must take into account these directives which are part of what is called natural law. There is here something supra-national, that is, of all times and all places, and that has imposed itself on successive generations » [9] That said, as regards the right of citizens to bear arms, it is clear from the above-mentioned evidence that it has been so everywhere since time immemorial. It is therefore a natural right in the sense of the definition.

In addition, the Count of Mirabeau had proposed that a Bill X be passed as part of the draft by the « Committee of Five » that was responsible for the official drafting of the Declaration, as follows : « Every citizen has the right to to own firearms in his home, and to use them, either for the common defense or for his own defense, against any unlawful aggression which would endanger the life or liberty of one or more citizens » [7]. The members of the Committee even added that it was a « natural right » by stating that, « it is impossible to imagine an aristocracy more terrible than that which would establish itself within the State, and by way of which some citizens would be armed and other not ; that all the contrary reasonings are futile sophisms contradicted by facts, since no country is more at peace and offers a better police than those in which the nation is armed » [8]. According to the authors, « natural law is composed of a number of superior and intangible principles, which apply not only to the authorities of a particular State, but to the authorities of all States. Thus, the legislator, when making laws, must take into account these directives which are part of what is called natural law. There is here something supra-national, that is, of all times and all places, and that has imposed itself on successive generations » [9] That said, as regards the right of citizens to bear arms, it is clear from the above-mentioned evidence that it has been so everywhere since time immemorial. It is therefore a natural right in the sense of the definition.

Indeed, both historically and legally, since the law of August 4th, 1789 abolishing the feudal regime of privileges, all French citizens have been granted the right to acquire and hold a recreational weapon (mainly for sport or hunting ), provided they do not use it in a prohibited manner. The law of April 30th, 1790 which allows the owners the freedom to hunt on their lands and even the farmers the right to destroy pests and repel them with firearms will afterwards confirm the acknowledgement by the National Assembly of the freedom to bears arms as pertains to hunting. In this respect, it is interesting to note that in parliamentary proceedings, even recent ones, everyone admits that one can find « with the abolishing of privileges, the introduction of a right to hunt. » Thus, only the misuse of a firearm must be sanctioned, only the damage resulting from these abuses must be repaired. The rule « the freedom of some people ends where the freedom of others begins » also applies to those who claim freedom as to those who consider certain of its effects to be detrimental.

In this regard, in 1764, the great jurisconsult Cesare Beccaria wrote in the illustrious « On Crimes and Punishments, » that, « Poor is the measure that would sacrifice a thousand real benefits in return for an imaginary or negligible embarrassment, which would remove fire from men because it burns and water because we drown in it, that has no cure for ills except their destruction. Laws prohibiting the carrying of arms are of such a nature. They only disarm those who are neither inclined nor determined to commit crimes (...). Such laws make things worse for victims and easier for abusers ; rather, they serve to encourage homicide rather than to prevent it because an unarmed man can be attacked with more confidence than an armed man. One should refer to these laws not as laws preventing crimes but as laws fearing crime, produced by the public impact of a few isolated cases and not by a deep reflection on the advantages and disadvantages of such a universal decree. » [10].

Aristotle in « Politics » [11], John Locke in the « Treaty of Civil Government » [12], Montesquieu in « The Spirit of Laws » [13], Alexis de Tocqueville in « Democracy in America I » [14], or Machiavelli in « The Prince » [15] also recognize the interest of the State and the citizen to have a weapon, since it is a guarantee of freedom and of the liberal and democratic character of government.

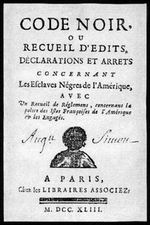

Thus, on the contrary, only the black code of 1685, nicknamed « Colbert, » forbade slaves from bearing arms ; while the legislation in force under the Vichy regime, such as Law No. 2181 of 1st June 1941 [16] , prohibited the possession, purchase and sale of arms and ammunition by Jews, and that Law no. 773 of August 7, 1942 [17] punished by death the possession of weapons and explosives by French citizens.

It should never be forgotten that « A people willing to sacrifice a little freedom for a little security deserve neither, and end up losing both » and that freedom is never earned, it exists only because citizens are ready to defend it for themselves and their children [18] !

Therefore, it should be acknowledged that every free man of healthy body and mind, with a clean criminal record, must have the right to acquire and own a firearm in the country which he is a citizen of ! Therefore, in a liberal and democratic political system, honest citizens, healthy in body and in mind, who own firearms legally, can legitimately demand that their right to property arms and their recreational right where concerns this firearm be respected.

Therefore, if we want the maxim « no one is supposed to be ignorant of the law » to apply, the directive should be amended as follows :

PROPOSED AMENDMENTS TO THE DIRECTIVE

| Article 1 Adding the following specifications in the preamble to Directive 1991 : |

| Article 2 To amend Article 2 of the 1991 Directive, as follows : Article 2 1. The European Union guarantees to European citizens the right to have materials, weapons and ammunition, in the pursuit of leisurely activities, such as hunting, shooting sports, collecting and renactor, as well as to ensure their self-defense in absence of law enforcement when their lives are threatened. The acquisition, possession, transportation, port, trade, manufacture, processing, transfer, import and export of equipment, weapons and ammunition may be regulated by law to the extent necessary to the general interest and insofar as this measure is indispensable to national security, public safety, maintaining of order and the prevention of offenses within a liberal and democratic political system. 2. This Directive is without prejudice to the application of national provisions relating to the carrying of arms or to the regulation of hunting and shooting sports or collecting by hobbyists and cultural and historical organizations in the field of weapons and recognized as such by the member-state on whose territory they are established. 3. This Directive shall not apply to the acquisition and detention, in accordance with national law, of arms and ammunition by the armed forces, the police or public authorities. Nor does it apply to transfers as governed by Directive 2009/43 / EC of the European Parliament and of the Council. |

| Article 3 To amend Article 3, as follows : Article 3 « Member States may adopt in their legislation stricter provisions than those laid down in this Directive, subject to the rights conferred on residents of the member-states by Article 12 (2) and respect for the rights guaranteed by the Charter of Fundamental Rights the principle laid down in Article 2 of this Directive. » |

| Article 4 Amend Article 5 as follows Article 5 1. Without prejudice to Article 3, member-states shall permit the acquisition and possession of Category A, B and C firearms to persons who have a legitimate reason and who : Article 5 Amend Article 10 (tertio) as follows Article 10(tertio) « 4. Member-states may notify to the Commission their national standards and techniques of deactivation applied before 8th April 2016, setting out the reasons why the level of safety guaranteed by these national standards and techniques of deactivation is equivalent to that guaranteed by the technical specifications for the deactivation of firearms set out in Annex I to Commission Implementing Regulation (E.U.) 2015/2403, as applicable to 8 April 2016. 5. When the Member-states notify the Commission in accordance with paragraph 4 of this Article, the Commission shall, no later than six months after such notification, adopt implementing acts determining whether the national standards and techniques of deactivation so notified guarantee that firearms have been rendered harmless with a level of safety equivalent to that guaranteed by the technical specifications for the deactivation of firearms set out in Annex I to Implementing Regulation (E.U.) 2015/2403, as applicable to 8 April 2016. Those implementing acts shall be adopted in accordance with the examination procedure referred to in Article 13b (2). » |

| Article 6 Amend Annex I as follows « (V) Category D - Firearms and other weapons that do not require a permit :

|

| Article 7 « The rules of execution (E.U. 2018/2403 of 15th December 2015) establishing common guidelines on deactivation standards and techniques to ensure that deactivated firearms are thus rendered irreversibly, will be rewritten within a delay of one year due to the disproportionate measures that it contains and especially contrary to the idea of adequate preserving of heritage » |

Explanation of the amending articles : Article 1. In application of the Charter of Fundamental Rights, the goal is to assert the right to property arms for leisure and for ownership. Article 2 : The aim is to guarantee these rights for sporting and cultural activities, Article 3 : If national laws are more stringent than the Directive, they must nevertheless respect the guarantees of the E.U. Charter of Fundamental Rights. Article 4 : It specifies that the possibilities of acquisition for valid reasons apply to categories A, B and C. This will allow to apply the art 6 §3) of the directive to allow collectors to own category A weapons. Article 5 : This is to allow States that have not yet communicated the equivalence of their technical standards within the deadlines set by the directive of 17 May 2017 to have the opportunity to do so.  Article 6 : To classify category D weapons of collection as well as to define that owning them without a license is legal. Article 7 : It seeks to have the Commission rewrite the regulation on the deactivation of arms by making it more in line with the preservation of heritage. |

[1] In accordance with the principle of proportionality, within the context of drafting the proposal for the adoption of the Amending Directive, it had duly taken into account of the objectives of the domestic market and the security imperatives pertaining to those objectives. The mere fact that the application of the amending directive may, under certain circumstances, lead to the confiscation of certain privately-owned firearms does not affect the right of ownership. The latter right could be restricted in the public interest and under the conditions as provided by the law : There is no fundamental right in E.U. law to possess firearms (Link to the opinion of Advocate General Sharpston published on 11 April 2019. Point 104.

[2] Louis Corneille, Commissioner of the Government, in his conclusions of the Baldy opinion (EC 10 Aug. 1917, No. 59855, published in the Lebon collection). This principle, which is a constant in France’s administrative case law, is enshrined in several judgments (CE 19 May 1933 Benjamin and TC 8 April 1935 French Action, CE 30 November 1923 Couitéas, CE Ass 2 November 1973 Maspero).

[3] Articles 2 and 4 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen of 26 August 1789, Articles 6, 51, 52, 53 and 54 of the E.U. Charter of Fundamental Rights, or Article 5 of the ECHR Convention, guarantee the principle of freedom as a natural right of the human person and its limitation as an exception justified by the need for public security, that is to say, needing to remain proportionate within the strict framework of a democratic society. Finally, the case law of the European Court of Human Rights, that considers European public order as an element of the defense of human rights against state restrictions in the service of common values, including respect for democracy and the rule of law is « a fundamental element" (ECHR, 17 February 2004, Gorzelick and Others v. Poland, case No. 44158/98, point 89).

[4] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract or Principles of Political Law, Book 1 Chapter I

[5] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract or Principles of Political Law, Book I Chapter VI

[6] Jean-Jacques ROUSSEAU, Du Contrat Social ou Principes du droit politique, Livre I Chapitre VI.

[7] Gazette National ou Moniteur Universel, n°42, 18 août 1789, p. 351.

[8] Préliminaires de la Constitution, Reconnaissance et exposition raisonnée des Droits de l’Homme et du Citoyen, Versailles, Imprimerie de Ph.-* De Pierres, Premier Imprimeur Ordinaire du Roi, rue Saint-Honoré, n°23, 1789.

[9] Michel De Juglart, Cours de droit civil avec travaux dirigés et sujets d’examens, Introduction personnes familles, Tome I, 1sup>er volume, 13sup>ème éditions, Montchrestien, 1991.

[10] Gazette National ou Moniteur Universel, n°42, 18 août 1789, p. 351.

[11] Aristote, La Politique, livre I, chapitre II, Editions Nathan, 1983.

[12] Dei delitti e della pene, di Cesare Beccaria, capitolo 40, False idee di utilità, edito da U. Mursia & C. 1973, a cura di Renato Fabietti , Cesare Beccaria, extrait du livre le Traité des Délits et des Peines, traduit de l’italien par l’abbé Morelet, 3ème éd., A Philadelphie M.D.C.C. L.X.V.I, chap. XXXVIII De quelques sources générales d’erreurs et d’injustices dans la législation et premièrement des fausses idées d’utilité, p. 129-130.

[13] Charles de Secondat baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu, L’Esprit des Lois, Chapitre II du Livre XI, Chapitre VI du Livre XI et Chapitre XIV du Livre XV, 1748.

[14] Alexis de Tocqueville, De la démocratie en Amérique I, partie I, chapitre II, p. 43 et partie II, chapitre IV, 1848, p. 24.

[15] Machiavel, Le Prince, Flammarion, 1980, Chap. XX, p.173-174.

[16] Article 15 du Code Noir ou Recueil d’Edits, Déclarations et Arrêts concernant les Esclaves Nègres de l’Amérique, Paris, Les Libraires Associés, M. DCC. XLIII.

[17] J. O., 8 août 1942) ou encore la loi n° 1061 du 3 décembre 1942 (J. O., 4 décembre 1942).

[18] J. O., 6 juin 1941